Western Africa’s history cannot be considered separate from the geopolitical, historical, religious and commercial contexts that tied its history into the political and religious vicissitudes of continental Europe, the Mediterranean basin and the Near East during the first ten centuries of the Christian Era.

The Byzantine Empire continued the Graeco-Roman tradition, given that it already had the advantages of an efficient administration, a prosperous economy and a highly developed cultural life in many sectors. From the second half of the sixth century up to the first third of the seventh century Byzantium opposed the Sassanid Empire, the other major power at the time, in continuous battle.

The Byzantine and Sassanid armadas, exhausted, found themselves unable to pose any resistance to the assaults launched by the Arab Muslims, after which, in the second half of the seventh century, Islam was founded in Arabia. The religious movement soon spread; from Coptic Egypt, it moved to Berber Maghreb, also with the penetration of Arab Bedouins towards Nubia, paving the way for the fall of the Christian kingdoms in the area.

Between 637 and 642, the Muslims overwhelmed Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine, Egypt and Libya.

This region occupied a key position in the Muslim world on a political and economic level. From Maghreb a conquest of Spain and Sicily was launched, with profound repercussions on the history of the Western Mediterranean and Europe.

This open entrance onto the Sahara and Sudan gave Northern Africa a particular importance for the economy of the Islamic world. Sudanese gold led to an economic development that allowed numerous Muslim dynasties to supplant their silver coins with gold money.

All this happened while Europe was divided into three main, and very different, spheres of influence: one part remained under the control of the Byzantine Empire; another part saw the Roman provinces of Western Europe dominated by various Germanic populations; lastly, in the regions situated to the east of the Rhine and north of the Danube, Germanic and Slavic populations ruled.

At the beginning of the eighth century the Arab-Berber conquest of Visigoth Spain cut off a considerable portion of the Latin West territory. The Franks succeeded in stopping the Muslim troops in Gallia, but the Arab incursions and raids continued for another two centuries along the coasts of Southern France and Italy, contributing to the growing climate of general danger in the Mediterranean basin.

In the rest of Europe, migrations towards the West of the Germanic populations paved the way for Slavic expansion, which developed mainly in two directions: to the south of the Danube towards the Balkans, and west towards the Central European territories.

Between the eighth and tenth centuries other people foreign to the Mediterranean world began to appear in Europe: the Normans, conquerors and merchant-adventurers who, coming from Scandinavia, attacked the coastal regions, and from there pushed into Europe’s interior.

Because of the Muslim presence above all in Northern Africa, the Mediterranean basin ceased to belong to one unified cultural area, as it had in the preceding millennium, and found itself divided into two zones – one European, or Christian, and the other Arab-Berber, each one with its own culture and destiny.

The Muslim world enjoyed great advantage thanks to its position in the heart of the ancient world. For its sheer immense size it was the only cultural area that had contact with all the other cultural areas: Byzantium, Western Europe, India and China.

Soon the Indian Ocean was integrated into the flourishing commercial maze that the Muslims progressively developed with China, Indonesia and Western Africa.

India played an important role on the Indian Ocean during the first millennium of the Christian Era.

In effect, if the documents illustrating the relations between India, Europe and Africa are few and far between, the archaeological remains attest to an intense exchange between the three continents. India has brought to light jewellery made with precious Baltic amber, African ivory and Mediterranean corals together with locally produced beads; at Arikamedu there are monochromatic beads, and at Cambay, faceted beads of agate and carnelian.

If the contacts between Africa, on the one side, and India and China, on the other, were primarily indirect, another region, situated in the eastern part of the Indian Ocean, marked some regions of Africa and the Arabian peninsula with the establishment of entire colonies, leaving a major imprint. Indonesia was not only a country of emigrants, but it was also, in the second half of the first millennium, a main player in maritime trade between the East, the Gulf of Arabia and the eastern coast of Africa, creating a monopoly on the trade of spices from South-east Asia and incense from Yemen.

Sudanese West Africa, seat of important state organisations from the sixth through fifteenth centuries, played a fundamental role in this international game of “risk”, supplying the raw material for all political and commercial power: gold.

Between the tenth and eleventh centuries the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad began to decline after flourishing from 750 to 909. For centuries Iraq had already been a cradle of glass production.

After losing control of Spain and Maghreb, the Abbasid Caliphate also had to abandon Egypt. In 641, Fustat (today a neighbourhood of Cairo) was founded and the Omayyads, who came from Damascus, in Syria, established themselves there between 661 and 750. Fustat shared in excellent glass production between the eighth and tenth centuries and which continued into the eleventh century under the Fatimid Dynasty, a Shiite dynasty that claimed direct descent from Muhammad through Fatima. Formed in Southern Tunisia, they later occupied all of Northern Africa.

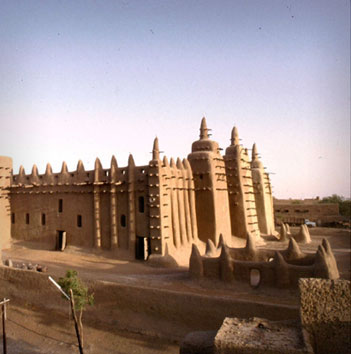

The spread of Islam south of the Sahara, and in particular in Western and Central Sudan, seat of important state organisations with flourishing capital cities like Awdaghust, Koumbi-Saleh (in Ghana), Timbuktu, Gao and commercial cities like Sidjilmasa, Djenné, Oualata and Tadmekka at the terminus of Trans-Saharan trade routes, was the result of the Arab conquest of Northern Africa and its consequential conversion to Islam, even though the process was different.

Only later, around the tenth–eleventh centuries, did the governing Sudanese class convert, following an Almoravid military operation in the Kingdom of Ghana. This led to the construction of large mosques and madras (Koranic schools), which culminated in the excellent Islamic university of Timbuktu. Pilgrimages to Mecca began and traced out new trade routes, uniting in a secure and stable fashion the coasts of the Arabian Gulf with the Southern Mediterranean and Southern Sahara.

The ease in conversion lay in the fact that this first wave of Islamic conversion contained numerous elements of various pre-Islamic faiths (Judaism and Christianity) native to those places, in addition to the surviving habits and beliefs of the Berber and Animist religions. This explains the presence of jewels, glass beads, idols and amulets of terracotta in the tombs of the Sudanese kingdoms, in the shadow of mosques, which were reference points for all the populations of the Sub-Saharan region between the eighth and eleventh centuries.

After the merchants, the second social group to convert to Islam was that of the chiefs and courtiers.

Even before the Almoravid era around 1010 a local chief in Gao (Kaw-Kaw) converted to Islam. In the same period, the King of Mallal, one of the most ancient chefferie of Malinke, also converted, due to a Muslim resident whose prayers had brought much-awaited rains.

Over the course of the eleventh century the advantages that Islam reserved for its followers grew increasingly evident, such that an ever greater number of the ruling classes and merchants followed the word and example of the Prophet.

The conversion of the sovereigns of the Empire of Mali to Islam occurred at the end of the thirteenth century, under the descendants of Sunjata.

The fact is that Mansa Uli, his son, succeeded him and completed the pilgrimage to Mecca during the reign of the Mamluk Sultan Baybars. After that the royal pilgrimage became a permanent tradition among the mansa, as the kings of Mali were called. The empire took its Islamic shape in the fourteenth century, under Mansa Mussa and his brother, Mansa Souleyman, beginning the construction of mosques and the development of Islamic knowledge.

A few ethnic groups were unified in their opposition to the spread of Islam in their territories; the Mossi in Boucle du Niger (the region to the south-east of Bamako) and the Bambara of the south-west. The material that has surfaced at Boni, in Mali, came from those regions, and was the fruit of Trans-Saharan trade, religious and cultural ties that united the Mediterranean coast to the Sahelian Islamic kingdoms. Glass beads are just one of the many bits of evidence of this connection. Religious, scientific and humanistic books in the libraries of the desert around Gao, Oualata and Timbuktu give some idea of the high level of these contacts that went well beyond mere trade.

Glass beads travelled, they were precious, sought after goods for trade. For centuries among African populations they represented important goods of trade.